A Legacy of Dirt

- by Barbara H. Lewis

- Mar 14, 2020

- 22 min read

Updated: Dec 6, 2021

They came for the dirt, my ancestors, the Steeles of Steeles Tavern. With fellow Scots-Irish immigrants, they sought out the fertile farmland of the Virginia backcountry, trudging down the narrow Valley corridor from Pennsylvania to Virginia in the 1730s, hoping to find a patch of fertile dirt to call their own. They ended up with several thousand acres of untilled pastureland and virgin forests in the Shenandoah Valley, part of a land grant from Richard III. They were the lucky ones, rewarded for their fortitude, prowess and disposable cash. After settling on the land that would one day become the small town of Steeles Tavern, my line of Steeles did not roam again for over two hundred years. They founded a legacy of dirt that lasted until my father left town.

I didn't grow up in Steeles Tavern. I have never resided on a farm. I am not dirt rich. Did I miss out on my legacy? What would dirt have to teach me?

What does it mean to be dirt poor? The phrase first turns up in America in the 1930s and may have something to do with the tragic years of the Dust Bowl. I picture dirty children and haggard parents standing in the doorway of an old shack. Dirt poor can also refer to a state of landlessness. If you're landless, then someone else can have power over you—over your food and water and shelter. Owning land in America provided personal freedom unknown to many immigrants when they lived back home across the seas. Wendell Berry writes that our “ancestors came here because they knew what it was to be landless; to be landless was to be threatened by want and also by enslavement." Landowners basically owned the people who worked the land. Immigrants caried the ancestral memory of serfdom.

In Northern Ireland, the Steeles might have been merchants or weavers, but when they reached the colonies they became landowners committed to farming in the Shenandoah Valley. They raised horses, sheep, and cattle, and grew oats, flax, corn, and wheat—along with a variety of vegetables they either brought from Ireland or borrowed from their native neighbors like "the three sisters" of squash, corn, and beans. Although the Steeles operated a flour mill and ran a tavern in the ensuing years, for six generations they depended on the land for their basic livelihoods. The dirt around Steeles Tavern fed my family for eight generations. The Steeles remained rich in dirt for two-hundred years.

My family farmed in Virginia for generations, but by the 1950s, they were relying on store-bought food. They left the dirt before leaving the land. Then my line left Steeles Tavern for good. After returning from soldiering in Japan during the war, my dad moved from Steeles Tavern, headed for college in Richmond, taking advantage of the GI Bill. With his mother, Edith, and sister, Jayne, Kemper Hawpe settled in Richmond where he raised a family. With his departure from the Valley, my line of the Steeles left behind their long heritage of the land. We brushed off the dirt of our former acreage and moved to a postage-size lawn in Richmond, Virginia.

Me, Mark, Dad, and Mom in our house on Comet Road

My family’s migration to the suburbs was typical of the times. The American landscape drastically changed during the 1950s as a massive population shift followed World War II. People chased jobs, moving away from the countryside where they’d been raised in order to live in cities and newly built suburbs. Thanks to GI Bill benefits, working-class veterans were able to afford new homes. The cookie-cutter houses that sprang up outside of metropolitan areas like Richmond weren't grand homes, but to folks like my Dad, who’d survived the Great Depression and World War II, these neighborhoods represented the changing American Dream of a good-enough job, a few kids, and maybe even a white picket fence.

My dad was content living in the suburbs. No hint of country life lingered on my father after he departed the Valley. “There’s no country on that man,” my mother’s friends told her when first meeting my father, surprised to find out about his country upbringing. Dad was no friend of dirt. He had grown up helping out on his grandparent’s farm in Steeles Tavern where he learned to hate sheep. The fleas kept him scratching, creating an unhappy boy who grew to be a man who harbored unpleasant memories of farm life.

I grew up in Tuckahoe Park, a neighborhood of identical brick ranch houses built after the war. Tuckahoe is a starchy plant that grows near riverbeds, a stable of the Powhatan Indians. Inexplicably, the streets in Tuckahoe Park were named for Santa’s reindeer. Our road was Comet.

Dancer and Donder and Rudolph laced through the neighborhood, but Comet Road was the longest street, meandering for a mile with a hill on one end and a dip in the middle. My friend, Ann, and I often rode our bikes down the hill to feel the wind on our faces and then we circled back the long way, keeping to the limits that the reindeer would allow.

Even though we lived in suburbia and not the countryside, I found places that felt wild to me. I spent many long, lovely weekends meandering in the fields and woods on my maternal grandmother’s old farm near the Chesapeake Bay. I spent summers in the undeveloped woods behind our house on Comet Road playing Cowboys and Indians with the neigbhorhood kids.

Parents didn't hover over their children so much back then. Mom believed that kids needed nature, and she not only allowed but encouraged us to spend time outdoors. She was a farmer’s daughter, and unlike my father, she loved dirt. Mom created a backyard where a kid could climb fences and run around barefoot as a gleeful resident of grass, flowers, trees, dirt, and pine tags. Thanks to my mother, our small backyard became a magical place for me.

Mom fed songbirds on the wooden platform beneath the dining room window. From inside, we could watch Evening Grosbeaks and Cardinals feeding. Tall pines shaded much of the yard. In a patch of sun, an island of tiger lilies and purple irises surrounded a birdbath. Ivy grew on the fence by the backdoor. At the very back of the property, Mom planted a row of holly bushes that served as a hedge surrounding a prolific vegetable garden. Springtime meant fresh strawberries and homemade shortcake. August offered swollen Concord grapes that we ate straight from the vine. When friends spent the night in the backyard with me—using my Dad’s army tent—we rose early to wash the dirt from the thin carrots of my mother’s vegetable garden and eat them for breakfast, exuberant with our self-reliance.

Except for mowing the grass, which he passed off to my brother, Mark, at the tender age of twelve, my dad left the tending of the yard and garden entirely to my mother. Dad never liked to work up a sweat. Mom, on the other hand, could dig in the dirt for hours.

Mom passed her love of dirt to me and through me to my daughters, who grew to love farm life. While the girls were in their teens, we bought a vacation house in the northern part of the Shenandoah Valley, which bordered on farmland, and this place kicked off a longing for the countryside in the girls. Our son, Christopher, was never keen on farming, but these days he enjoys hiking and camping in the Pacific Northwest.

My son rock climbing in Washington

Not everyone likes farm life or digging in the dirt. All that mud and manure and the unpredictability of animals, as well as the solitude of country life, can disturb suburban and city kids. Some people raised on farms are eager to leave farm life. Almost two-hundred years ago, the inventor Cyrus McCormick, a neighbor of the Steeles and the man who overturned worldwide agricultural practices, absolutely hated farm work. This seems fitting. Cyrus’s invention enabled men (like my dad) to shake off the dirt of the farm and head towards the city (or suburbia), taking jobs in offices and factories—anyplace that let them escape the muddy fields and annoying insects, and hard, hot, physical labor that they’d experienced on the farm.

Beneath a hot sun, Cyrus McCormick’s father, Robert McCormick, swung a grain cradle to cut wheat while Cyrus and his sweaty, thirsty brothers walked behind, picking up the slain wheat stalks and tying them into bundles. Extended kin, neighbors and paid laborers, and sometimes enslaved people helped with the harvest. Everyone had to hurry. Harvest season lasted only a few days. If bad weather prevailed, an entire crop could be lost. Robert McCormick had worked on a reaping device and quit. In 1831, twenty-two-year-old Cyrus, with the help of Jo Anderson, a talented enslaved man belonging to the McCormicks, set about improving Robert McCormick's reaper. A few months later, Cyrus demonstrated his new reaping machine on my ancestor John Steele’s oat field.

The Steels and McCormick families had long been neighbors, intermarrying several times before Cyrus was born. At the time of the demonstration, Cyrus’s Uncle George was married to John’s sister, Jenny Steele. My great-grandfather, Walter Searson, eventually managed the McCormick home-place, and my grandmother, Edith, was raised on the McCormick Farm. I recommend visiting this beautiful farm, which is open to the public.

McCormick farm

My grandmother, Edith Steele Searson, and her sisters, Fair and Mildred

On the day of the first public demonstration of the reaper, the neighbors gathered around to watch the new-fangled contraption cut down the Steele’s corn. My great-great-great-grandparents, Eliza and John Steele, stood on the side of the cornfield gawking. According to the court testimony of Eliza, everyone thought the machine “a right smart curious sort of thing” but no one “believed it would come to much.”

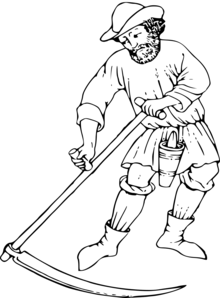

The Steeles and their neighbors were soon proven wrong. McCormick’s machine changed agricultural practices worldwide. Reaping had always been back-breaking work. Since the beginnings of agriculture, farmers had harvested grain with a sickle—a heavy, curved, saw-toothed knife with a wooden handle. They bent over to grab a few stalks before swinging the sickle close to the ground. A man working all day might finish two acres. The scythe was invented in 1655, radically changing the process of harvesting. With this long, curved blade (that was attached to a wooden stock) a skilled farmer could cut more than three acres in a day. Three acres! A cradle of curved wooden fingers was eventually added to the scythe. But beginning in the 1850s, farmers around the world set aside the sickle, scythe, and grain cradle for Cyrus McCormick’s harvesting machine.

With the new harvesting machine, a farmer walked beside a horse and wagon that carried the mechanical cutter. The horse did most of the work. A large revolving reel swept up the grain. A comb of teeth caught the grain, holding it in place. A divider separated the grain to be cut from the grain left standing. The blade sliced from front to back and sideways. The platform caught the grain as it fell. The farmer raked the grain off the platform. Binders tied the stalks into sheaves. Could it get any easier?

Cyrus McCormick's Havesting Machine

After the reaper caught on with farmers, a trend toward labor-saving devices took hold. Farming practices shifted from the maintenance of sustainable small farms to a more industrialized orientation to the land. Productivity became the focus of farming; what was once the result—harvesting a product—became the goal. Small diversified farms couldn’t compete with large, industrialized farms that focused on one crop. Big farms swallowed up small farms. The demise of the family farm can be credited in part to the purchase of large, expensive farm machinery like Cyrus McCormick’s mechanical reaper.

Whether they wanted to or not, farmers began walking away from the land, abdicating their long-held legacy of dirt. Farm laborers also had to look elsewhere for work. Many left to find factory jobs in the cities. The mechanical harvesting device freed up northern soldiers to fight in the Civil War, ironically helping to defeat McCormick’s Valley neighbors. The fertile, highly productive farmland of the Shenandoah Valley had served as the “Breadbasket of the Confederacy”—until Sheridan destroyed over two thousand barns full of wheat and hay, and seventy mills housing flour and wheat--and stole four thousand head of cattle and three thousand sheep. Ouch! Many former enslaved men and women, like those who had worked my family’s land, left the Valley after the war. Some drifted north in search of work, severing ties to the land.

Among the letters and papers that I have inherited, I found an enormous 1858 financial ledger that once belonged to William J. Hopkins, a son-in-law of John Steele, my ancestor. Hopkins ran a store in Steeles Tavern before the Civil War. The debts of over four hundred farmers are recorded in this book, including the debts and repayments of many of the Steeles. William Steele owed $49.12 on July 1, 1859. On the same day, John Steele owed $22.29, Martin Steele $12.01, Marriott Steele $3.61 and James Steele $1.11. A page devoted to Francis Steele records expenses running from 1858 to 1862. Wash Steele paid 42 cents “cash in full” on July 13, 1860. Milly Steele paid off a balance of $3.50. Loose pages torn from a separate accounting book are tucked inside the Hopkins’ store ledger. In 1873, David Steele bought two hundred bushels of apples and a half-pint of brandy. In 1866, a Steele heifer sold for $32; a cow and her calf for $30.

I’m not sure if Hopkins collected all the debts owed to him. During the war, northern troops burnt his store to the ground. He moved his family to California.

The agricultural economy of the Valley rebounded during the 1870s. A decade later, the number of horses, milk cows, beef cattle, and sheep had recovered to pre-war levels, which was important because farmers needed the manure to augment the soil. According to Professor Koons of VMI, “Nearly every farm diary or account book from the period includes details regarding farmers’ hauling of large quantities of manure to their fields…”

Farmers cared deeply about manure. Founding father, John Adams, had been quite enthusiastic about the magic of manure. To make “choice manure” he recommended twenty loads of seaweed, and twenty loads of marsh mud, and ashes from the Potash Works, and weeds from the garden, and a year’s worth of household trash, and dung from horses, oxen, cows, hogs. Pile a heap of this concoction in the desired location and let it rest for three months. Dig up this pile of once-living organic matter and make another heap. Leave this second heap alone until the ground freezes. When needed cart the new dirt to the plot of land you have chosen to augment. Mix and repeat.

To better understand my ancestors and how they spent their time and energy, I’ve been reading a lot about dirt. I found one book to be irresistible: “Dirt: The Ecstatic Skin of the Earth." Dirt as poetry seems fitting. The science of soil should lean toward the mysterious.

All dirt is made of sand, silt, and clay. A perfect combination of sand, silt, and clay will create luxuriant loamy soil. Depending on your area of the country, you will find the following classifications: sandy clay, silty clay, loamy sand, sandy loam, sandy clay loam, clay loam, silty clay loam, or silty loam. If that list isn't poetic, I don't know what is. In the Shenandoah Valley, my ancestors found deep, well-drained sills with a subsoil of clay loam, shale-silt loam, and sandy loam lying overtop a limestone floor.

Limestone and dolomite sediments are the common bedrock in the Shenandoah Valley because an ancient sea once flooded the area. Dirt is history. The youngest rocks in the Shenandoah are from river, lagoon, and beach deposits. The geologic story of the Valley includes an inland sea and the formation of two mountain ranges. The worn-down Appalachians, which are the second mountain range to occupy the Valley, once rivaled the Himalayas.

The origins of dirt is important because the basic mix of soil can’t be easily changed. But adding organic matter improves soil. My mother once dumped a truckload of manure on our lawn. Our neighbors graciously indulged her, aware of her green thumb. The smell deeply impressed me. We won “Yard of the Month” that summer, a source of pride for the whole family.

Within healthy dirt fed by organic matter, you will find flatworms, mites, springtails, and beetles devouring bacteria and fungi, as well as earthworms ingesting organic molecules and pooping out dirt. All organic matter eventually turns into humus. Humus provides a friendly habitat for microflora and microfauna.

“Humus is magical,” my eldest daughter told me recently.

"Did you know that scientists don’t claim to know what humus is exactly," I replied, heady with my recent readings. "Only what it does."

“You love humble scientists," she reminded me.

"Humble scientists allow for mystery," I replied. "They leave a place for magic."

Mysterious, magical humus emerges from the aftermath of plundered plant and animal matter. Recycled life. Former flesh and fauna--and manure and urine--anything that was once organic goes into the creation of humus. Humus feeds the living. Everything alive depends on humus.

To understand the processes occurring in the soil that feeds us, follow the ions. Plants nibble on nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, calcium, sulfur, magnesium, carbon, oxygen, and hydrogen, and also the trace minerals: iron, boron, chlorine, manganese, zinc, copper, molybdenum, and nickel. Plants consume the particles they need as ions—which is a molecule with an electric charge due to the loss or gain of one or more electrons, in case you’ve forgotten your Middle School Science. If I understand the science correctly, these electrons make the processes of life possible. Nutrients come into the plant by exchanging positive ions for negative ions. “Look here!” says the plant to the dirt. “Take these negative ions and give me those positive ions. I’m hungry! And I need to pee!” Root hairs pump hydrogen ions into the soil through proton pumps. These pumps form an electron transport chain. Picture a long line of people passing buckets of dirty water through a mountain tunnel. At the end of the tunnel, the bucket is refilled with clean, nutritious water and passed back up the line. Only really fast.

My farming ancestors knew about the relationship between plants and the living soil even if they didn't know about ions. They fingered the plants, walking up and down the rows of corn and wheat, examining plants to see if they were stunted, or if the leaves had yellowed. They knelt to examine the beans and squash and tomatoes growing in their kitchen gardens, looking to see if the roots were shallow, undeveloped, or rotten. When dark stains lingered on their fingertips after touching the dirt, they were pleased. If their fingers remained clean, they might make a tea by soaking dry, aged manure in water for a few days and then applied this mixture to the plants. They touched and sometimes tasted the dirt. Put their nose to the sweet-smelling humus and took an exuberant sniff.

Wendell Berry contends that small farmers who know their land are better skilled at preserving the resources their land has to offer. Well-tended family farms can last for many generations. The Steels farmed the same land for six generations. They might not have known about the science of soil but they knew their dirt. Otherwise, they would’ve failed at farming long before my father left Steeles Tavern.

Economic variables make it hard to make a living as a farmer in the Valley today. The next generation may not be able to stay on the family farm. The good news is that some people are becoming homesteaders. Homesteaders often engage in small scale textiles and craftwork and other sources of revenue to supplement farming with a goal of self-sufficiency. They try to mix it up, using multiple enterprises to make ends meet and remain on the farm.

Hobby Farms are also becoming popular. Hobby farmers usually have another source of income and so they don’t have to make a profit on the farm. They want the lifestyle of a small farmer and yearn to eat homegrown food and keep goats or chickens or pigs. But even hobby farmers need to know their dirt, or else what’s the point? Why go through the bother of tilling and fertilizing, planting and watering, if you’re not interested in the results? But learning how to farm can seem like time-traveling to people who've never farmed before. Most of us don’t have a clue about serious food production. “We don’t know beans about beans,” wrote Barbara Kingsolver during her year-long experiment as a hobby farmer in Virginia. A year when she produced most of her food.

I’ve been fantasizing about buying a Hobby Farm. The Steeles Tavern area boasts several possibilities this week. There’s a lovely three-bedroom home listed with a four-stall barn and tack room. But I don’t know much about horses. A few miles north in the town of Greenville, there’s an income-producing property with many options, including a facility for commercial cattle scales, cutting pens, and chutes for trading and sorting cattle. No, thanks. I’ll steer clear of steer. I could relocate to a seventy acre stretch of rolling pastures and hardwood forests, complete with a tractor and brush hog—a powerful rotary mower. Who knows? I might relish making new paths through tangled underbrush. The big boss lady riding her brush hog. Bring it!

All I need to figure out now is how to farm.

You can learn how to farm on YouTube. I recently came upon Meredith Bell’s adventures in farming, which began by visiting farmers’ markets in NYC. A wild dream of farming grew from a love of fresh food. Bell took her life savings and bought twenty acres of farmland in California where she taught herself how to farm by studying videos online. During her first year as a farmer, her efforts derailed due to flooding. She ended up raising chickens.

Before buying a Hobby Farm, I should shop around for land with good drainage. Notice if water ponds on the surface after a hard rain, or if the soil seems too compacted. Is the ground a sponge or a sieve? When I press dirt between my fingers, does it come apart in clods, powdery flakes, or rounded crumbs? Are my fingers appropriately stained? To prevent soil erosion, I should plow across the field tracing the natural contours, especially on sloped land. The small ridges left from the plowing will slow down runoff. Rows of trees and shrubs prevent erosion by blocking the wind, and so I should be sure to plant trees twenty years ago.

I might grow corn like the Steeles. A cyber tutorial gives helpful instructions. Plant seeds two inches deep and about five inches apart. Rows should be separated by about a yard. If the soil’s healthy I can forego fertilizing when planting, but I should be sure to give the seedlings ample water. Thin the emerging four-inch stalks to a foot apart. Do not damage the roots when weeding! Keep the corn watered. Try mulching. Harvest when tassels begin to turn brown and cobs start to swell. Kernels should be full and milky. Take the corn home and stick a few cobs in a pot of boiling water. Corn never tastes as sweet as when freshly picked and cooked. My mother's family ate only hot buttered corn for supper after the first day of the corn harvest.

Rotate your crops! Year one: grow corn. Year two: grow oats. Year three: grow wheat. Year four and five: grow clover that brings nitrogen back into the soil. In the vegetable garden: Year One: grow tomatoes. Year Two: grow onions. Year three: grow beans. Year four: grow cabbages. Year Five: take a long holiday and think about retiring.

According to various websites, sheep are relatively easy to handle, compared with cows and pigs. In spite of my dad’s loathing of sheep, I enjoy the picturesque creatures from afar. If I make the plunge into sheep farming, I should keep in mind that sheep don't need a perfect pasture. Although sheep love grain, peanuts, and apples they will happily munch on brush, grass, or weeds that grow from poor soil. In warm months, sheep will require some shade. A former sheep pasture provides a fertile spot for growing crops.

Manure!

When selecting sheep, I should check to see if their eyes are bright and clear. Are teeth worn or missing? Hooves trimmed? Too fat or too thin? When buying an adult ewe, I must be certain the udders aren’t lumpy. Do not chase sheep! When frightened, they will bunch together and run. A sheep-herding dog might be a good idea.

I have several wool blankets from the Steele’s sheep-raising days. I’m presently making a quilt from one of them, which has already begun to worry me. How do you wash wool that’s over a hundred years old? "Very carefully!" says the clerk at my local quilt shop. But what else should I do with it? Leave the wool in the attic for the next hundred years?

Even if most hobby farmers don’t plan on supporting themselves by farming, I might need to take out a small loan to have fun on my farm. Because inside a hobby farmer’s shed could be a chainsaw, ax, hatchet, maul, digger bar, pitchfork, mattock, wheelbarrow, pruning shears, ear notcher, sheep shears, post driver, post maul, corn sheller, troll, garden cultivator, grease gun, calf weaner, shovel, wire fence stretcher, hay hooks, posthole digger, lopping shears, a wire fence cutter, scythe, wheat sickle, beet knife, dandelion digger, tractor wrench, drawknife, wheel hoe, and pruner saw.

When Dave Steele died in 1747, he only left his son, Robert, an iron plow.

I wonder what my ancestors would think of hobby farmers? Would they find the idea of farming for fun ridiculous?

(Yes, that's right. I think of my ancestors in the present tense.)

I don't know what my ancestors would say about Hobby Farms but I know what one of my daughter's think of them. In October, I stood on the porch of her farm cabin on the East coast in looking across the snowy field toward the faraway hills, the leaves still tinged red and gold.

“There’s a big difference between homesteading and hobby farms,” she says, indicating her strong preference for the homesteading option.

My sister-in-law has come with me from her home where we recently enjoyed a Lewis family reunion. (My husband’s side of the family.) One of the Lewis cousins told me that Mama Lewis, my children’s great-grandmother, kept chickens and a milk cow and even pigs in her large backyard—even though she lived within the limits of a large town. I wonder what Mama Lewis’s neighbors thought of her perky roosters?

The chickens on my daughter's homestead have chosen to stay cozy and warm in their coop today, but we’ve already hung out with the goats, taking pictures of young Neville and stately Hayduke with his long beard. My granddaughter names all the farm animals, usually drawing upon fictional characters, often from Harry Potter or the works of Tolkien.

When I first met the chickens several years ago, a rooster immediately flew up and sat on my hat. "You should feel honored," my daughter told me. "Aragorn doesn't usually take to strangers." Another time, Padma Patil, a frisky young goat, jumped on my shoulders when I knelt on the ground, taking me by complete surprise! I ended up doing what anybody would do in a similar situation. Goat yoga!

My daugher and her hsuband aim to be homesteaders, but my also daughter works in town. She leaves for work wearing muck boots and then changes into “sensible shoes” at the office.

They hope to plant blueberries and apples. But the vegetable garden remains a disappointment. “We’re going to keep trying,” my daughter says with a shrug. “We need better soil.”

Since I've been reading about what makes for good soil, we talk about composting. I lament that her father is concerned about attracting rodents to the yard with a compost bin.

“If you use the right worms,” she tells me. “You can compost inside the house. There's no smell."

“Worms?” Karin repeats. “Inside the house?” She shudders. “I don’t think so.” Karin shares her brother's distaste for creepy, crawly critters.

“You could get an indoor composting bin," my daugher suggests. "You could hide it in a closet. Dad would never know it was there.”

I picture myself sneaking into the laundry room to dump banana peels into a composting bin full of red worms. Why must I have to choose between marital harmony and rich, black dirt?

The autumn cold chases us into the house where we are served steaming bowls of homemade onion soup. On the shelf, I spy a book on homesteading that I gave to my daugher years ago. “I loved that book,” my daughter tells me. “But it’s not practical.” Now that she’s determined to turn her dream of farming into a reality, she wants specific, useful advice. The nuts-and-bolts of farming. “I still like looking at the pictures though," she says.

Back in the hotel room, I wonder what my dad would think of his granddaughter's new American dream—the goats and the chickens and the homesteading. Although Dad died when my daughter was a teenager, he knew her as a thoughtful and passionate young person. I don’t think he would be surprised to find her living on a farm.

Our Eastcoast daughter isn't the only one of our children who wants to live on a farm. All through college, our eldest daughter, who now lives on the West coasst, worked on an organic farm in Virginia. After graduating, she apprenticed with a woman farmer, hoping to discover the secrets that would provide for success as an organic farmer. But after years of bending and kneeling and hoisting, she realized that she needed a stronger body—and a husband who wanted to farm. She wouldn’t be able to farm alone.

But our daughter who lives near us on the West coast continues to flirt with the idea of farming. She keeps looking at farming properties on the outskirts of the city. When I show her a clip of her sister’s farm in Vermont, she shouts, “I’m so jealous! She’s living ‘Little House on the Prairie.’ I wish we could do that!”

“Little House on the Prairie” might be a national fantasy—a picture-perfect farm story hiding the precariousness of farming life. On a farm, so much is out of your control. Nature can be cruel. The precariousness of the economy has crushed many small farmers. The farm crisis of the 1980s decimated family farms.

Time to face the truth! I won't be sinking our retirement fund into a farm. I won't be choosing to buy a farm in Steeles Tavern. I’ve reached my sixth decade and that merciless fact precludes heavy lifting and continuous hard labor. I can’t leave my family in Seattle. But neither my aging body nor my inability to move back to my home state of Virginia has kept me from pouring over farms for sale in Washington. I can still dream! Some of these farms are offered as Hobby Farms. There’s a blueberry farm that looks enticing and several properties with adequate acreage to do whatever I please. The most intriguing opportunity offers two separate homes and “16 acres of peaceful tranquility…nestled in the rich farmland…with views of mountains, sunsets, tulips, and fertile farm fields.” Maybe my eldest daughter will end up making the great leap into hobby farming or homesteading, and Brian and I could join her and her family on a small parcel of green acerage. We could grow parsnips and raise sheep and embrace our legacy of dirt! (We could also hire younger, stronger people to do some of the work.)

I’ll keep you posted.

Even if I turn my fantasy farm into a reality, I appreciate that growing my food is a choice for me. If I don’t toil the land, I will still eat. I can choose to not farm and instead spend my free time writing, drawing, practicing yoga, and playing with my grandkids. If I don’t have the responsibility of running a farm, I can travel to see friends and family on the Eastcoast. I’m glad I can opt-out of a legacy of dirt. I think my ancestors would want their descendants to have that freedom. I’m certain my father would have wanted me to have such a choice.

If my grandchildren and great-grandchildren don’t come to own land as adults, I hope they can find some publicly-owned dirt. I hope there’s still plenty of publicly owned dirt for them to find. I hope they hike and camp and rock climb and kayak. I hope they fall in love with trees. Perhaps they will grow food in their suburban yards, or join a community garden in their chosen cities. Maybe one or two of them will become a hobby farmer or homesteader and grow most of their food and raise farm animals. My descendants might keep alive our legacy of dirt.

Is that a fantasy? I certainly hope not.

Passing along our legacy of dirt

Bibliography

Berry, Wendell . Bringing It To The Table:On Farming and Food. Berkley, CA: Counterpoint, 2009.

Buff, Sheila, edit. Traditional Country Skills: A Practical Compendium of American Wisdom and Know-How. Guilford, Connecticut: The Lyons Press, 2001

Hess, Anna. The Ultimate Guild to Soil: The Real Dirt on Cultivating Crops, Compost, and a Healthier Home. New York: Skyhorse Publishing, 2016.

Logan , William Bryant. Dirt: The Ecstatic Skin of the Earth. New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 1995.

Montgomery, David. R. and Anne Bikle. The Hidden Half of Nature: The Microbial Roots of Life and Health. New York: W.W.Norton and Company, 2016.

Murphy, Elizabeth. Building Soil: A Down-To-Earth Approach. Minneapolis, MN: Cool Springs Press, 2015.

Reid, Keith. Improving Your Soil: A Practical Guide to Soil Management for the Serious Home Gardener. NY: Firefly Books, 2014.

Wirzba, Norman, edit. The Essential Agrarian Reader: The Future of Culture, Community, and the Land. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. 2003.

Internet

Koons, Kenneth E. “Our once beautiful but now desolated Valley.” Shenandoah Valley Battlefields Foundation, 2015

http://www.shenandoahatwar.org/our-once-beautiful-but-now-desolated-valley/

Parikh, Sanjai J. & Bruce R. James. "Soil: The Foundation of Agriculture," Nature Education, 2012.

https://www.nature.com/scitable/knowledge/library/soil-the-foundation-of-agriculture-84224268/

Thorne, Holly."New Farmers Guild to Starting To Starting a Farm in Virginia"

F&M Bank Blog: In In the Community, 2019

https://www.fmbankva.com/start-farm-virginia/

"The Hidden Costs of Industrial Agriculture." The Union of Concerned Scientist, 2008

https://www.ucsusa.org/resources/hidden-costs-industrial-agriculture

Weingarten, Debbie. "Quitting Season: Why Farmers Walk Away From Their Farms." Civil Eats, 2016.

https://civileats.com/2016/02/12/quitting-season-why-farmers-walk-away-from-their-farms/

Colonial Williamsburg, "Historic Farming" https://www.history.org/Almanack/life/trades/traderural_corn.cfm

_____________________________________________________________

Photos of Farms in Steeles Tavern, VA:

https://www.google.com/search?q=pictures+of+farms+in+Steeles+Tavern&sxsrf=ACYBGNS4aPqDjtAyK6RICh-zesxaiO_JTA:1570743874495&tbm=isch&source=iu&ictx=1&fir=_x-cLrxNd-WpmM%253A%252C4Jt1inn9Z5GKfM%252C_&vet=1&usg=AI4_-kRTg0elfZFhVJnHOa5xJwfBY2useQ&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjyg7D11JLlAhXLsJ4KHctsA5UQ9QEwBXoECAYQFQ#imgrc=ErEFLYmyu00kYM:&vet=1

Comments